The vomit machine!

How do scientists study the transmission of viruses from person to person? Why, with a vomit machine of course!

Norovirus is a group of more than 30 related viruses that can cause vomiting and diarrhoea, with infections sometimes requiring hospitalisation and occasionally causing death in vulnerable groups such as the elderly.

About a quarter of ‘noro’ infections are obtained by consuming contaminated foods or water, but it is most often spread between people in close contact with each other.

A long-held theory is that norovirus can be ‘aerosolised’ through vomiting, meaning that small particles containing norovirus can become airborne when someone throws up, transmitting directly to a nearby person or contaminating surfaces. (Fun fact: Noro can still be detected in dried vomit after six weeks.)

But norovirus aerosolisation by vomiting had never been proven. Enter norovirus expert Lee-Ann Jaykus, a professor of food science at North Carolina State University and scientific director of NoroCORE (Norovirus Collaborative for Outreach, Research, and Education).

To test the theory, researchers in Jaykus’s lab needed a controlled way to observe and study vomiting over and over again. They needed a vomiting machine.

Unsurprisingly, a vomiting machine is not something that can be found on eBay, so the researchers had to design and build their own. A graduate student from the civil, construction and environmental engineering department provided the construction know-how, while data on vomiting was provided by a gastroenterologist.

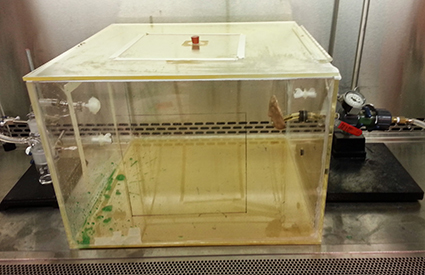

Working together, the researchers created a machine that is essentially a scaled-down version of the mouth, oesophagus and stomach — made of tubes and a pressure chamber that passes through a clay face to give it the correct vomiting angle. The machine is designed to let researchers control the pressure and volume of the vomit, in order to mimic a range of natural vomiting behaviours. The device is enclosed in a sealed Plexiglas box and placed under a biosafety hood.

Liquid solutions of different viscosities or thicknesses were used as ‘artificial vomitus’ to reflect different stages of digestion. A bacteriophage called MS2 — a virus that infects E. coli but is harmless to humans — was substituted for norovirus.

After extensive testing of the machine, they began using it for formal experiments, which showed that the virus was indeed aerosolised.

And although the amount of MS2 aerosolised as a percentage of total virus ‘vomited’ was relatively low (less than 0.3%), vomit from infected people contains millions of particles, meaning the actual amount of virus particles aerosolised during a single vomiting event ranges from only a few into the thousands, perhaps more.

“And that is enough to be problematic because it only takes a few, perhaps less than 20, to make a susceptible person ill,” Jaykus said. “This machine may seem odd, but it’s helping us understand a disease that affects millions of people. This is work that can help us prevent or contain the spread of norovirus — and there’s nothing odd about that.”

The research was published in the PLOS ONE journal.

Food creations on the shelf for shaping up and flying away

As we start into summer, there have been some interesting dairy creations hitting the shelves for...

Six on the shelf: Summer treats by the block load

Summer treats hitting the supermarket shelves include truffles by the block, ice creams for road...

What's new on the shelf

From classic reinspired ice cream to West African flavours in a jar and whiskey aged in a gaol,...