From cassava to KFC: global standardised diet threatens local crops

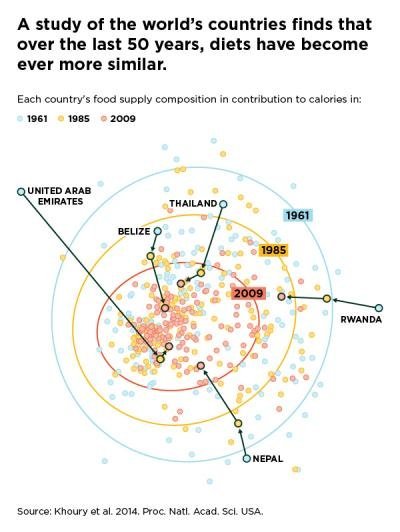

Globalisation isn’t just affecting the clothes we wear and the music we listen to - it’s also dictating what we eat. A new study of global food supplies has confirmed what experts have long suspected: in the last 50 years, human diets around the world have grown more and more similar - by a global average of 36%.

This trend shows no signs of slowing, the study reveals, and could have major consequences for human nutrition and global food security.

“More people are consuming more calories, protein and fat, and they rely increasingly on a short list of major food crops, like wheat, maize and soybean, along with meat and dairy products, for most of their food,” said lead author Colin Khoury, a scientist at the Colombia-based International Center for Tropical Agriculture (CIAT), which is a member of the CGIAR Consortium, a global research partnership for a food-secure future.

“These foods are critical for combating world hunger, but relying on a global diet of such limited diversity obligates us to bolster the nutritional quality of the major crops, as consumption of other nutritious grains and vegetables declines.”

The study authors call for urgent action to promote healthier, more diverse food alternatives to prevent the growing incidence of obesity, heart disease and diabetes, which are strongly affected by dietary change.

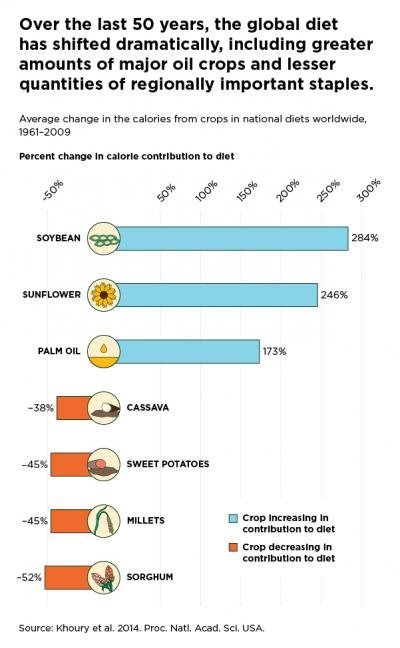

Crops of regional importance - like sorghum, millet, rye, sweet potato and cassava - are being overtaken by wheat, rice, maize and potato. The study authors are particularly worried that the emerging ‘standards global food supply’ also consists of energy-dense food crops like palm oil, soybean and sunflower oil.

Wheat is a major staple in 97.4% of countries and rice in 90.8%. Soybean has become significant in 74.3% of countries.

Many locally significant grain and vegetable crops have lost ground to these crops. For example, the nutritious tuber known as oca, which was previously widely grown in the Andean highlands, has declined significantly in both cultivation and consumption in the region.

“Another danger of a more homogeneous global food basket is that it makes agriculture more vulnerable to major threats like drought, insect pests and diseases, which are likely to become worse in many parts of the world as a result of climate change,” said Luigi Guarino, a study co-author and senior scientist at the Global Crop Diversity Trust.

“As the global population rises and the pressure increases on our global food system, so does our dependence on the global crops and production systems that feed us. The price of failure of any of these crops will become very high.”

The authors noted a curious paradox: as the human diet has become less diverse on the global scale, many countries - particularly in Africa and Asia - have actually widened their menu of major staple crops, while changing to more globalised diets.

“In East and South-East Asia, several major foods - like wheat and potato - have gained importance alongside longstanding staples like rice,” Khoury said. “But this expansion of major staple foods has come at the expense of the many diverse minor foods that used to figure importantly in people’s diets.”

These dietary changes are driven by a number of forces. Rising incomes in developing countries has enabled consumers to buy more animal products, sugars and oils. Urbanisation in many countries has encouraged greater consumption of processed and fast foods.

This is further compounded by factors such as trade liberalisation, improved commodity transport, multinational food industries and food safety standardisation.

However, the researchers noted some positive trends, such as in Northern Europe, where evidence suggests that consumers are buying more cereals and vegetables and less meat, oil and sugar.

The researchers suggest five actions to foster diversity in food production and consumption to improve nutrition and food security:

- Actively promote the adoption of a wider range of varieties of the major crops worldwide.

- Support the conservation and use of diverse plant genetic resources.

- Enhance the nutritional quality of the major crops on which people depend.

- Promote alternative crops that can boost farming resilience and make human diets healthier.

- Foster public awareness of the need for healthier diets, based on better decisions about what and how much we eat as well as the forms in which we consume food.

“International agencies have hammered away in recent years with the message that agriculture must produce more food for over nine billion people by 2050,” said co-author Andy Jarvis, director of policy research at CIAT and leader for climate change adaptation with the CGIAR Research Program on Climate Change, Agriculture and Food Security (CCAFS), which CIAT leads.

“Just as important is the message that we need a more diverse global food system. This is the best way, not only to combat hunger, malnutrition, and over nutrition, but also to protect global food supplies against the impacts of global climate change.”

The comprehensive study used data from the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO) and encompassed more than 50 crops and more than 150 countries from 1961 to 2009.

The study is published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

Mimicking meat: texture science for plant-based meats

Stanford engineers are developing an approach to food texture testing that could pave the way for...

What's new on the shelf in the lead-up to Christmas

Chocolate baubles, fruity snacks, Milkybar milk and instant coffee with a cool twist are some of...

A vision of a food trend

Research at the University of Sydney tested the reactions of more than 600 people making food...