Printed biosensors to monitor freshness of meat and fish

Iowa State University researchers are using aerosol-jet-printing technology to create graphene biosensors that can detect histamine, an allergen and indicator of spoiled fish and meat.

And it’s not just for meat or fish; bacteria in food produce histamine so it could also be suitable for determining the freshness of other food.

It turned out the sensors — printed with high-resolution aerosol jet printers on a flexible polymer film and tuned to test for histamine — can detect histamine down to 3.41 parts per million.

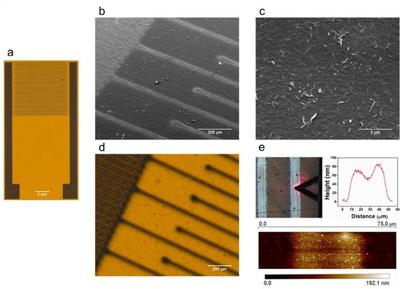

Making graphene practical on a disposable food-safety sensor is a low-cost, aerosol-jet-printing technology that’s precise enough to create the high-resolution electrodes necessary for electrochemical sensors to detect small molecules such as histamine.

“This fine resolution is important,” said Jonathan Claussen, an associate professor of mechanical engineering at Iowa State University and one of the leaders of the research project. “The closer we can print these electrode fingers, in general, the higher the sensitivity of these biosensors.”

Recently published online by the journal 2D Materials, the US researchers’ paper describes how graphene electrodes were aerosol jet printed on a flexible polymer and then converted to histamine sensors by chemically binding histamine antibodies to the graphene. The antibodies specifically bind histamine molecules.

According to another one of the research project leaders, Carmen Gomes, an associate professor of mechanical engineering at Iowa State, the histamine blocks electron transfer and increases electrical resistance. That change in resistance can be measured and recorded by the sensor.

The researchers believe the concept will also work to detect other kinds of molecules.

“Beyond the histamine case study presented here, the (aerosol jet printing) and functionalisation process can likely be generalised to a diverse range of sensing applications including environmental toxin detection, foodborne pathogen detection, wearable health monitoring, and health diagnostics,” they wrote in their research paper.

For example, by switching the antibodies bonded to the printed sensors, they could detect Salmonella bacteria, or cancers or animal diseases such as avian influenza, the researchers wrote.

Claussen, who has been working with printed graphene for years, said the sensors have another characteristic that makes them very useful: they don’t cost a lot of money and can be scaled up for mass production.

“Any food sensor has to be really cheap,” Gomes said. “You have to test a lot of food samples and you can’t add a lot of cost.”

Claussen and Gomes know something about the food industry and how it tests for food safety. Claussen is chief scientific officer and Gomes is chief research officer for NanoSpy Inc., a start-up company based in the Iowa State University Research Park that sells biosensors to food processing companies.

They said the company is in the process of licensing this new histamine and cytokine sensor technology.

It, after all, is what they’re looking for in a commercial sensor. “This,” Claussen said, “is a cheap, scalable, biosensor platform.”

Six beverage trends predicted for 2026

Demand for customisation, 'protein-ification' and sustainable storytelling are some of...

Making UHT processing less intensive on energy

A nutritional beverages company was seeking a more sustainable way to produce UHT beverages using...

Tasty twist for chocolate alternatives

Food scientists develop two novel flavour-boosting techniques to transform carob pulp into a...