Listeria doesn't like the light

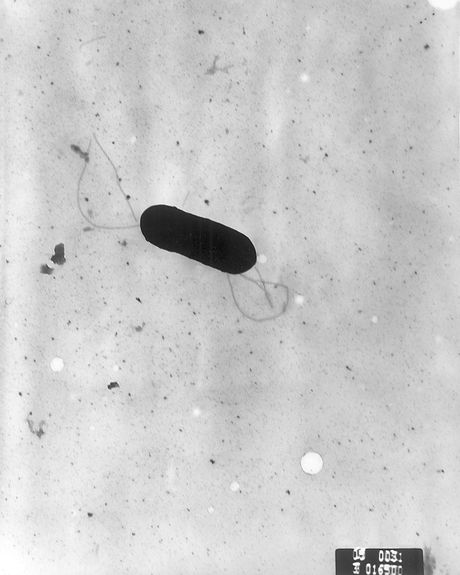

In interesting new research, researchers at Umeå University in Sweden have now discovered a new property in Listeria that the food industry may be able to exploit to prevent the spread of the bacterium. Listeria doesn’t like the light!

Even though Listeria monocytogenes is ubiquitous in the environment, by far the most likely source of infection with the bacterium is via the ingestion of contaminated food products.

For healthy individuals, the Listeria bacterium doesn’t usually cause much more than a few days of gastro. However, the same is not true for the elderly, newborns, those with compromised immune systems or for pregnant women, where the bacterium can be very dangerous. In these individuals the bacterial infection can be invasive and spread to the bloodstream and hence to the brain. This carries a mortality rate of 20–30%. If a pregnant woman is infected, the bacteria can spread to the foetus and cause miscarriage.

Listeria monocytogenes, named after the British surgeon Joseph Lister, is a particular risk in unpasteurised dairy products and charcuterie. Unlike most foodborne disease causing bacteria, Listeria is not deterred by low temperatures and can grow in refrigerated food.

In interesting new research, researchers at Umeå University in Sweden have now discovered a new property in Listeria that the food industry may be able to exploit to prevent the spread of the bacterium. Listeria doesn’t like the light!

When Listeria is exposed to light, the bacterium activates protective mechanisms.

In his dissertation, doctoral student Christopher Andersson also described the discovery of two new molecules that combat the pathogenicity of the Listeria bacterium. The researchers also studied how the molecules can be used to prevent the bacterium from causing disease.

“Hopefully, this new knowledge on how light and these small molecules affect the bacterium can, in future, be used to prevent the spread of Listeria and help treat listeriosis,” said Christopher Andersson, doctoral student at the Department of Molecular Biology at Umeå University and author of the dissertation.

A digital publication of the dissertation is available here.

Processing method to lower oil in French fries

Researchers have explored a microwave frying method that could help food manufacturers modify...

Food metal detector solves dairy product effect

Food safety specialist Fortress Technology explains how product effect can interfere with...

Reading Between the Lines: A Smarter Way to Verify Allergen Safety

Allergen management remains a priority consideration for food manufacturers in Australia and New...