Napping Listeria: bacteria that hide in cells

Listeriois is a serious but uncommon disease caused by consuming foods that have been contaminated by the Listeria monocytogenes bacterium. Individuals with an impaired immune system, the elderly, new-born infants and even farmed livestock are among those most at risk, and it has the ability to cause severe clinical symptoms possibly resulting in death.

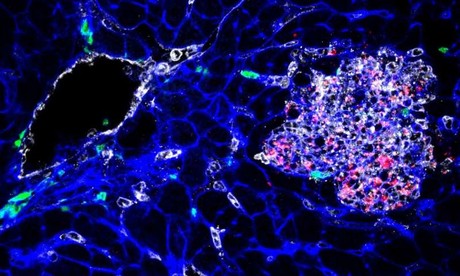

Published in PLOS Pathogens, INRA scientists collaborated with their colleagues at Institut Pasteur and demonstrated that L. monocytogenes can generate dormant intracellular forms that could be unknowingly harboured by their host.

The Listeria bacteria can invade different cells in the body, including the epithelial cells in the intestine, liver, brain and placenta. When it reaches the cell’s cytoplasm, it multiplies and uses a network of cell filaments — called the cytoskeleton — to travel and spread into other cells. This enables L. monocytogenes to disseminate throughout the tissues in the body.

The researchers studied the behaviour of L. monocytogenes by creating an in vitro experimental model using cultures of human epithelial cells. Through this model, they discovered that L. monocytogenes is able to change its lifestyle when it infects the cells of the liver and placenta for several days.

The bacteria gradually stop producing the protein (ActA) that helps them spread using the cytoskeleton of infected cells. Since they are trapped in the vacuoles, their ability to resist antibiotics increases and they can reactivate themselves in a form that can be disseminated again.

It can enter host cells while they are dividing and go undetected on the culture media usually used for diagnostic tests. Although viable, the bacteria are in a non-cultivable state.

The in vitro results have revealed that humans or animals could be carriers of dormant L. monocytogenes, displaying no symptoms for up to three months, until they are reactivated. Therefore, if listeriosis occurs a long time after eating contaminated food, this may explain why it is often difficult to identify the source.

The scientists suggest that this research could encourage further investigation which may result in the development of new therapeutic and diagnostic strategies. It may also help manage the risks related to a microbial food contaminant.

Kraft Heinz appoints Steve Cahillane as CEO

Steve Cahillane will join Kraft Heinz as CEO on 1 January 2026.

Mars receives final approval for its Kellanova acquisition

The European Commission has given final approval for the merger, paving the way to unite the...

Tetra Pak Processing Equipment SIA acquires Bioreactors.net

Tetra Pak has acquired the Latvia-based company to help strengthen its processing expertise,...